JTICI Vol.7, Special Issue (5), pp.93-115

Conservation and Tribal Ecology: An Analysis of a Tiger Conservation Project in Mizoram

DOWNLOAD PDF

Conservation and Tribal Ecology: An Analysis of a Tiger Conservation Project in Mizoram

Abstract

Rising environmental problems, such as climate change and endangered wildlife species, are directly related to the state’s development schemes which put immense pressures on the environment and its natural resources. To address these problems, conservation organizations, institutions, and government agencies have implemented conservation strategies which are both widely accepted yet, at the same time, have unintended consequences. The outcomes of project-based conservation practices vary in different ways in different geographical locations. In the global south, conservation models are often antagonistic received by local people, who consider them as top-down colonial impositions that disrupt their lifeways. This paper critically engages and analyses the impact of conservation projects on tribal peoples and their ecologies. It investigates whether this kind of conservation project operates based on the merits and needs of the local environment and people or merely satisfies the demands of environmental institutions and actors with conservationist agendas. I argue that the outcome of this kind of conservation practice may paradoxically be de-conservation and political instrumentalization to violate human rights and tribal groups. This paper is based on doctoral fieldwork on a tiger conservation project in the state of Mizoram.

Introduction

The imposed concept and practices of conservation projects and their outcomes vary in different geographical locations. The Dampa Tiger Reserve (DTR) project in Mizoram is one such example. This is simply due to the conceptual and policy shortcomings of the conservation project framework. It fails to incorporate the local conservation ethos of people and their socio-culturally and historically sustainable management of resources, whose resilience through periods of considerable social and political change remains unexplored. Indeed, the imposed conventional ideas of conservation practices are considered top-down, instrumental, forceful, and colonial which ruptures local tribal ecologies and disrupts local lifeways. The conservation project framework is often taken for granted by world powers and institutions for its proposed goals of addressing climate change, threats to the environment, endangered species, and the protection of biodiversity. However, it operates in the larger context of socio-ecological, socio-political, and cultural relationships contextualised by state, market, and social relationships and realities in different parts of the world. Thus, it is creating more challenges about how to sustain both biodiversity and local tribal ecologies.

This paper questions the sacred views of the conservation model to address the environmental problems and challenges. I argue that it is a ‘conservation discourse fantasy’ which follows James Ferguson’s (1990:320) critique of “development discourse fantasy.” He argues that it is not enough just to analyse development’s success and failures: what matters is the outcomes or what he refers to as “sociological ends of these projects”. Similarly, in the context of conservation projects, what matters are the sociological and environmental outcomes. If the outcomes are displacements, human rights violations, forced alienation from tribal ecologies and socioeconomic frictions with tribal communities, then the achievement of environmental goals must be placed in the broader context of burgeoning socio-ecological crises—and deemed a failure. This paper analyses the DTR project which has created such crises and ruptured the fragile human-nature interactions typified by tribal ecologies. It has created massive changes in tribal people’s relations to land, forest, and wildlife, all the while perpetuating local and regional socio-political power dynamics between different ethnic or tribal identities in Mizoram and Northeast India (couched as conservation discourses).

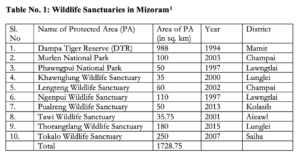

The conservation framework is based in an exclusionary process that misses the complex relationality that exists between humans and animals, the human habitats and the forests, and the sacred landscapes. This relationality with nature in which the ecosystem is formed is discrete and largely invisible within this framework. This article discusses the local ecological system representing fluidity and continuity of life for people and wildlife between the hills and the plains. It provides context for how the present configurations of society and the environment historically evolved over time in Mizoram—for example, how bamboo flowerings directly shaped Mizoram’s socio-political and ecological histories. The paper achieves this by focusing on a prominent tiger conservation project, the DTR (Dampa Tiger Reserve), a tiger project without any tigers. According to the Environment, Forests & Climate Change Department, Government of Mizoram 2023 records the following are the statistic of wildlife sanctuaries in the Mizoram state.

The Dampa Tiger Reserve Forest (DTR) encompassing 988 square kilometers and covering 57.15% of the total areas of the wildlife sanctuaries of the state. It is the biggest conservation project in the state dedicated to tigers without any tigers.

What is Conservation?

Conservation can be best understood through the state-led projects and community-based practices to conserve biodiversity, wildlife, forest, and ecology. Worldwide, forests and wildlife were historically considered both opportunities and challenges to economic development and expansion of permanent and settled agricultural practices. In the process the wildlife is either exploited for commercial purposes or killed, resulting in extinction and near extinction of many wildlife species. Hence, the conservation project model was a response to such environmental crises. For instance, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines conservation as any area where “the highest competent authority of the nation having jurisdiction over it” is vested with responsibilities to protect that area (Poirier and Ostergren 2003).

On the other hand, community-based conservation is not about a decentralised conservation approach but is rather about conducting conservation outside of state purview. It is about the practices of the people who are already well adapted to environmental conservation for centuries and are not in need of projects to conserve biodiversity and ensure sustainability. The Apatani tribe of Ziro Valley of Arunachal Pradesh is a classic example of community-based diachronic local conservation practices of nature and ecology. The Apatani tribe rejected the idea of conservation or ‘reserve forest’ and are displeased with the attempts of the government of Arunachal Pradesh to declare their community forest as a reserve forest under the 1976 Forest Act. The Apatani tribe argues for their inherent rights to control the forest which they have been conserving for centuries until the present. They are also apprehensive and reject the idea of mapping and surveying their area by arguing that their boundaries already exist and are recognized under traditional systems. Moreover, they argue that there are no conflicts or disputes at the intertribal and intratribal level (S. Chatterjee et al., 2000), in distinction to other tribal communities, such as the Gaddis of the Western Himalayas, which are caste heterogeneous and have contested appeals to the state for the inclusion of five Scheduled Caste communities (Christopher 2020).

The Ziro Valley of Apatani tribe is under the tentative list of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage for its cultural landscape (UNESCO, 2014). The landscape is listed for its unique agricultural technique that includes optimum land use by the Apatani tribe and their efficiency in conservation of the valley. It is stated that “Ziro Valley presents an example of how co-existence of man and nature has been perfected over the centuries by the Apatani civilization” by the Indian representative to the UNESCO. The Apatani tribe worships nature and their relationship with and celebration of nature regulates their cultural practices. This relationship between nature, culture and humans is of a timeless universal value. The Indian representative described the valley as, “Canopy cover of the mountain ridges around the valley has increased, the paddy fields are as placid as it was and so are the bamboo gardens. Apart from widening of traditional narrow streets, the old charm of the villages is intact. Characteristic socio-religious structures like lapañ, nago and babo are still the centers around which life revolves.”

The advocacy attempts to impose the idea of ‘reserve forest/areas’ by national and international organizations like WWF to the Apatanis demonstrate the inherent interest of state and non-state actors without considering local people and the ecology. The reasons could be to forcefully insert the dominant idea of conservation with the intent to reject the local conservation practices and their material interest in the implementation of conservation projects. The Apatanis also expressed distress about the Talley Valley Wildlife Sanctuary in Arunachal Pradesh which impacted them as well and strongly believing that it is an extension of their clan-controlled forest land, and the government must have consulted them before declaring it as a wildlife sanctuary.

Tribal ecologies and conservation practices are not only with forest areas but include agricultural practices whereby the indigenous knowledge system and sociocultural values play a significant role in shaping the rural economy (Wangpan et al., 2014). For instance, the ‘exotic varieties’ of food crops are not suitable to their local soil, which is more suitable for local varieties. They are against subsidies being provided to attract cultivation of such varieties (Chatterjee et al., 200). In fact, they have exceptionally high outputs of rice which are 60 to 80 units per unit energy input (P.S Ramakrishnan, 1992). This is also far superior to the traditional wet cultivation of rice of the Indian plains and even other national contexts, such as the Philippines (Nguu and Palis, 1977).

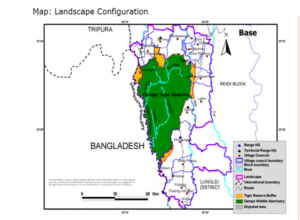

Conservation discourse fantasy and the DTR

The Dampa Tiger Reserve (DTR) is located at the tri-junction of Bangladesh and two Indian states viz., Mizoram and Tripura and is the largest Protected Area (PA) in the state of Mizoram by occupying 4.68% of the state’s geographical area. It is in the Mamit district of Mizoram state and is surrounded by the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh to the west, the Indian state of Tripura, to the north, and Mamit Forest Division to the south and east of Mizoram. The total area of DTR is 988 km² of which, 500 km² is as Core or Critical Tiger Habitat and 488 km² as Buffer Area. The DTR covers an area of 57.15% of the total areas of the wildlife sanctuaries of the state. The Dampa region (in which the tiger reserve is situated) is a part of the north-eastern hill region landscape and is located at a unique junction of Indian, Indo-Malayan and Indo-Chinese biogeographical realms (Mani, 1974). The landscape is also a part of the Indo-Burma Global Biodiversity Hotspot, recognized as an Endemic Bird Area and is one of the Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World.

Map 1 Landscape of the DTR

In and around the DTR forest, there are mainly three indigenous communities such as the Mizos, Chakmas and the Reangs. The Mizo means the people of hills or the highlanders and represents the Mizo language speaking tribes. The Chakma and the Reang identify themselves as distinct from the Mizo tribes and do not speak the Mizo language. The Mizo tribe practices practice Christianity, the Chakmas practice Theravada Buddhism and the Reang are known as a Vaishnavite Hindu tribe, although a significant minority practice Christianity.

3.1 A tiger project without any tigers

The Dampa Wildlife Sanctuary was challenged by the affected people of the Chakma tribe in the Guwahati High Court (in the Assam state) and the notification was quashed by the court on the 11th of August 1982 in favour of the people. The judgement states that “the impugned orders are not sustainable in law because the state did not follow the legal procedures such as lack of people’s consent, publications in local newspapers and the Official Gazette.” On the 23rd of March 1985, the state issued a notification to declare it as the Dampa Wildlife Sanctuary with an area of 681 Km.²

As per the official records, the number of tigers in the DTR forest was between four and seven between the years of 1993-2010. However, there were continued efforts to locate more tigers to justify the project’s significance. According to the Mizoram government, World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and Aaranyak, a society for biodiversity conservation, there were three confirmed tigers inside the DTR based on their DNA study in 2012. The Udayan Borthaku, Head of the wildlife genetics programme of Aranyak, stated that “out of nine tiger scats for the DNA analysis, three scats are confirmed as tigers.” However, as per the Dampa Tiger Report of April 2012, out of the 26 scats from Dampa that they are analyzing in the lab, nine (9) are confirmed tigers’ scats, eleven (11) as non-tigers and six (6) failed to produce any results (Chakma, 2013).

As per the DNA studies of tiger scats, the state claims the presence of tigers but without any conclusive or confirmed numbers of tigers. Since 2006, the government with the help of WWF has installed 35 cameras inside the reserve forest to capture footage of tigers but failed to do so. In its tiger report of 2012, the government promised to install more cameras (Chakma, 2013). Finally, in 2020, the state accepted that there are no tigers in the DTR which is reported by different news media. According to the state government, the absence of tigers in the DTR is due to poaching which cannot be true as there were no tigers since its inception. During my master’s degree fieldwork in six Chakma and Reang villages including interviews with the forest guards of the DTR, there was no such evidence that supports the presence of tigers in the DTR forest. According to the state government’s annual reports and plans, it states that “not much is known of the distribution of tigers and their co-predators in the buffer area of Dampa although there are frequent sightings of leopards and wild dogs from this area.”

The camera trapping method to capture the images of tigers and to record the presence of tigers continued till 2019-2020 but without any success. In state government’s annual plan and reports namely, the tiger conservation plan of the DTR forest (2013-14 to 2022-24), the camera trapping method captured the following: five cat species such as common leopard, clouded leopard, marbled cat, Asiatic golden cat, the leopard cat and two other cat species such as the jungle cat and the fishing cat, based on secondary information. It also captures the western hoolock gibbon (Mittermeir et al. 2009), rare stump-tailed macaque, northern pig-tailed macaque, nocturnal Bengal slow loris and the common rhesus macaque. There are other wild animals such as the gaur, sambar, serow, barking deer and wild boar and small carnivores and mammals such as the Chinese/Burmese ferret badger, hog badger, small-clawed otter, yellow-throated marten, large and small Indian civet, Himalayan crestless porcupine, brush-tailed porcupine, Malayan giant squirrel, and red flying squirrel.

The claims for the presence of tigers and their scats for the DNA studies are highly controversial. For instance, during my graduate field research, I came across about a well-known (among the villagers of Silsury, Hnahva and Rajivnagar) incident before the year 2012. The incident was about two DTR forest guards who were caught by an underground/militia group known as UPDF, inside the forest in Bangladesh with cameras. Initially, they were suspected to be of Bangladesh government’s spy and were questioned, beaten and their cameras were chased by the UPDF. To confirm the authenticity of the incident, I interviewed a forest officer in Mizoram who initially denied it and questioned the relevance of the query to my research. Finally, admitted by stating that his predecessor “Mr. X wanted to see tigers, but people misled him with the believe that there are tigers in Bangladesh, so he sent forest guards to take photographs”. In my doctoral fieldwork, during my interactions with the staffs of the Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), the apex national intelligent bureau just like the USA’s CIA. I was told that the DNA samples produced by the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF), Aaranayak and DTR office, were collected from a militant group based in Bangladesh. In return, they were paid a huge amount of money and free passage of weapons with the help of DTR authorities.

Apart from the camera trapping and DNA studies, the state government also deployed other methods to examine and probe the presence of tigers in the DTR such as the predator-prey experimentation with domestic cows. In the year 2010, the forest department left three cows into different areas of Keislam, Seling and Chiklang (name of places inside the DTR) deep inside the reserve forest with the assumption that the tigers will kill and eat them. After a couple of weeks, the cows were found alive and healthy. However, the government neither recorded nor made this report public.

Indeed, none of my interviewees from all three communities (Chakma, Mizos, and Reangs) including staffs from the forest department denied the presence of tigers in the DTR. For instance, in my doctoral fieldwork, one of my focus groups was senior citizens or elderly from the village Silsury and Hnahva, strongly believe that there were and are no tigers since the last three decades. To the question of “have you ever seen a tiger in the DTR?” and they unanimously responded with the word “never”[1].

These clearly illustrates that there are no tigers in the DTR. It was only in 2020, when the state government accepted that there are no tigers in the DTR–news that was reported by various news media. According to the state government, the absence of tigers in the DTR is due to poaching. This cannot be true as based on the above empirical evidence there were no tigers since its inception. According to the state government’s annual reports and plans, it states that “not much is known of the distribution of tigers and their co-predators in the buffer area of Dampa although there are frequent sightings of leopards and wild dogs from this area.”

Displacement from the DTR

The Dampa Wildlife Sanctuary was declared on 20th January 1976 by the government of Mizoram with an area of 180 sq. miles. It was challenged by the affected people led by Mr. Jaladhar Chakma in the Guwahati High Court and the notification was quashed by the court on 11th August 1982 in favor of the people. The judgement also states that “the impugned orders are not sustainable in law.” However, again, on 23rd March 1985, the state issued a notification to declare it as the Dampa Wildlife Sanctuary with an area of 681 Km² and to displace fourteen villages.

In 1988 the then Deputy Commissioner (DC), Aizawl District, H. Hauthuama, was appointed to inquire into the claims, rights, etc., of persons dwelling inside the Dampa Wildlife Sanctuary. In the report, the DC reported that “as far as could be ascertained from the record of state government, no right of the above-mentioned people is found to exist in the said area. The people have been doing Jhuming or Jhum cultivation in the area for the last few years. Out of the fourteen Jhumia villages inside the Sanctuary, four villages namely Serhmun, Dampa Rengpui, Silsury and Avapui are established villages with a large population and situated on the peripheral portion of the Sanctuary.” The D.C (Deputy Commissioner) also suggested to reduce the boundaries of the Dampa Wildlife Sanctuary to 462 Sq. km and to consider giving financial assistance of about Rs 2000/- (25.56 USD) per household.

My focused group members during my doctoral fieldwork were former staffs of the forest department, who were also the village level works of the DTR project. They recollect that Jhum cultivation was allowed inside the DTR with conditions from 1990 to 1993-94. The conditions were doing plantations of forest fruits trees, teaks, and other such trees and plants which are both edible to wild animals and have commercial values. However, for Jhum cultivation permission is required from the forest department and without permission, anyone cultivating Jhum is liable to be fined, arrested, or at least harassed. From 1990 to 1994, there were six cases where Jhum fields were burnt down and the Jhummias (Jhum cultivator) were taken to the district court for doing Jhum cultivation. And after 1994, Jhum cultivation was banned, and people were restricted from entering the forest without permission. However, at that time there were no legal cases of hunting.

They further recollect that in those times, especially in the 1990s, they had to face the fierce opposition of the people who did not consider them friends and treated them as enemies. For instance, in 1993, as directed by the then Field Director, Lokhi[2] and his colleagues from the forest department demolished a garden of Mr. Lalit Chakma, who cultivated inside the DTR forest areas. His garden consists of vegetables, bananas, pineapple, jackfruit and so on in the Keislamdor or Hugisorador. His garden falls in the Hugisorador (a small stream inside the core areas of the DTR) and the river Sajek borders between India and Bangladesh. Upon learning the news, Mr. Lalit came down to the village with a handmade gun to kill Lokhi. After knowing the information, he and his colleagues left their house and the village and returned only after a week.

Since 1994, until my focus group quit working with the forest department, there have been many cases of local villagers hunting wild animals and cutting trees/woods. In those days, cutting trees was for the construction of houses and other domestic uses. In 1994 when a villager named Gondha Dhan Chakma from Silsury (now migrated to Bangladesh) was arrested while cutting trees inside the buffer areas of the DTR. When he was caught, his knives and other belongings were seized. He was cutting trees and bamboo to repair his house for which he was denied permission. At that time, his arrest was sympathized with by the villagers who supported him with any help that they could offer. In the end, he was released with bail but then he fled away from the village to Bangladesh and never came back.

Similarly, there was a case in 1995, when a former village council leader and his colleagues were caught and arrested for cutting wood inside the DTR. The reasons for cutting wood were like the previous case which was to fix their houses. The villagers were terribly angry and prevented their arrest. They appealed to Mr. Liansoma, the then Forest Minister of the state, to get back their wood. Upon their appeal, the Forest Minister came to Pukzin village (a neighbouring Mizo village) and organised a meeting whereby he requested Pala, the then Field Director, to return the wood. However, the Field Director did not accept it and finally, the woods were burnt down to ashes. Though they did not get back their wood, the environment in the villages was against the forest department. It was a very tense situation and difficult for forest department workers to enter the forest for duty. However, there were constant pressures from the authority to perform their duty and there were many cases of joint operations in the DTR by the forest guards, state police and ground-level forest workers (also known as M.R – Muster Rolls) belonging to Chakma, Mizo, and Reang tribes. In such operations, in 1996, a few villagers were caught while clearing forest for Jhum cultivation and a case was filed against them in the District Court. The court settled the case with some amount of money as a fine.

Eventually, the villagers could not carry out any activities in the Reserve, from cutting wood or bamboo to fishing and hunting, and to Jhum cultivation. According to the villagers of Silsury, though many of their communal lands were taken away in the 1990s by the reserve forest, they still had enough areas, though not abundant like before. So, they continue doing Jhum cultivation in their available communal land, but the Jhum cycle has reduced from 7-10 years to almost 3-5 years. They believe that this has impacted the fertility of the land and do not have enough production like before.

Taking away most of their communal land, and putting restrictions and strict rules and regulations in the reserve forest has also gradually impacted their livelihood and foods including meats, fish, etc. In the 1990s, and before, the rice or the ration supplies available were not used by the people except kerosene. People say that the families who must eat the rice supplied by the government indicate their poverty or inability to produce enough rice from their cultivation.

As time passes by and when they can no longer access the lands where they used to cultivate, the dependency on government-supplied food has increased and the demand for government schemes. Schemes like Indira Awaz Yojana (IAY) for housing, New Land Use Policy (NLUP) for planting commercial crops, Multi-Sector Development Schemes (MSDP), Border Areas Development Programme (BADP), and competition to get Below Poverty Line (BPL) ration card, are in huge demand among the people. Under the government schemes such as the IAY, an amount of 20 to 30 thousand rupees was given to construct a house, for NLUP an amount of rupees 30 to 50 thousand to cultivate market-based crops such as acre nuts, fisheries, etc., and the BPL cardholders can access rice for rupees 2 (two). However, not all the eligible people get it and only those who get selected by the village council members who represent the elected political party are available.

In 2005-06, when the line of core areas of Dampa Tiger Reserve (DTR) was extended to the Aviapui stream next to the village Silsury, problems started once again. With the boundary extension, more than 90% of village communal lands were taken away without any kind of accessibility to it. Villagers can neither access the riverbanks or valleys for any kind of agricultural activities, nor can-do fishing or hunting.

The Impact of displacement on people and the local ecology

The DTR project has systematically created crises at multiple levels, from socio-livelihood to the environmental crisis. It is a classic case of failure to conserve anything. The project has stopped people’s interaction with nature by physically displacing them and restricting them to enter or undertake any kind of activities. This displacement also led to the displacement of wildlife.

The displacement resulted into forcefully changed the livelihood practices of people from subsistence to market-oriented, which has created a crisis of food. This consequently puts immense pressures on the environment, especially the fish, wildlife, and the forest resources. Therefore, it has become a conservation project to de-conserve in the name of conservation, ultimately serving the political economy of the state.

One of the wildlife scientists T. R Shankar Raman (2001) who conducted an extensive field study in the Dampa Tiger Reserve Forest argues that to conserve the environment there is a need for people and nature to live together, instead of without each other. His study also includes the impact of jhum on bird and wildlife species and concludes that jhum cultivation leads to an increase in bird diversity. It also leads to a mosaic of dense bamboo and diverse secondary forests. Raman further noted that shifting cultivation may be better than establishing monoculture plantations for conservation, especially bamboo and the secondary forests that harbour many forest bird species.

People used to practice two types of livelihoods. One is jhum cultivation, and another is vegetables and fruit gardening on the river valleys during winter. The products from these livelihood activities are shared with wildlife in the forest and rivers. For example, the birds and wild animals get their share of the fields from the crops and insects available to them. In the jhum fields, varieties of rice crops, vegetables, fruits, flowers, and other domestically consumed food crops are produced. Production of cotton, til (or sesame), and chillies are exchanged in the market to buy daily necessities like oil, clothes, kitchen utensils, and other such which they cannot make. In the river valleys, rice is not produced but other crops of vegetables, fruits, flowers, and so on. Tobacco and mustard are the only commercial products to sell in the market and meet their household needs. In fact, after the agricultural seasons, people abandon the agricultural fields allowing many additional vegetables to continue to grow. It literally belongs to the wild animals, and people often come back just to collect vegetables on daily chores. This is the reason there was an abundance of wildlife in the times (especially before displacement) when people were allowed to continue their livelihood practices. The displacement of people thus also resulted in the displacement of wildlife.

Wildlife hunting and fishing was a communal exercise done either collectively or individually. If an aanimal is hunted with a gun, then its meat is shared with others with a space defined by the sound of the gunshot. If the hunting is based on traditional methods, then sharing is based on the distances that the news of the kill covers, except that the hunter gets a thigh portion of the hunt, and the rest is shared with others. The news of a hunt is widely shared if it is a big wild animal. The hunt cannot be brought home, and it must be cut into pieces and distributed among the people. If the hunt is brought home without distribution among people, then it is believed that the wild animals’ dead body also brings a bad omen to the family members including death. However, both fish and wild meats were never exchanged for money. People hunt and fish only for domestic consumption purposes and not for the market.

The DTR project banned the people from any kind of fishing and hunting, rendering both a so-called unlawful act under the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972. This has led to a crisis and demand for food. The crisis and demand resulted in the creation of hunting groups to hunt inside the DTR forest. The meat of a deer costs from rupees 500 to 600 (6 to 7 USD). A healthy buck deer weighs at least 40 kilograms and above. In neighboring non-Chakma villages, based on the field study carried out with the local hotels, one of the owner’s incomes is more when they get wild meats supplied by the so-called illegal hunters. According to the hotel owners, the hunters are from different communities and villages. The meats in highest demand are wild boar, deer, and buck deer. They get wild meat once a week and there are no fixed days or times about its availability. Earlier, people carried out fishing with traditional methods including using nets, but now people are even using electrocution. According to the local people, this method is the only easy and quick way to get fish now. At the same time, not all the fish die after electrocution, and it is believed that they either die after a few days or their reproduction capabilities are damaged permanently. The other popular method is blasting in the river and killing the fish.

The DTR conservation project has also introduced commercial and monocrop plantations. In the period between 1990 to 2000, the DTR allowed jhum cultivation with the condition of growing commercially valuable trees such as teak. The Mizoram state under its flagship New Land Use Policy (NLUP), introduced palm oil and teak plantations covering hundreds of hectares of land area. In the year 2013-14, the Mizoram government identified 1,01,000 hectares for oil palm cultivation and over 17,500 hectares were already permanently deforested. As per the annual reports published in 2018 by the department of environment, forest, and climate change, the main source of revenue in the state of Mizoram are broomsticks, anchiri (Homalomena aromatica), cane, sawn timber, and other non-timber forest products (NTFP). In the Mamit district alone where the DTR covers its geographic area, the forest department generated annual revenue of rupees 3378821 or 42436 USD.

The numbers and figures clearly demonstrate the systemic exploitation of the forest and its resources and its immense pressures on the environment. However, this system includes both legal and illegal processes under the Indian Forest Act, 1927. For some social groups it is illegal, and for others it is legal. One of my interviewees who belongs to the Chakma community and a former Jhum cultivator with a family of eight explains it very well. He has four children, his wife and his parents in the family living in the same household. He has four acres of land for broom cultivation from where his family earns between Rupees 30,000 to 40,000 (383 to 511 USD) per annum. In the month between June to September, he goes inside the DTR to collect roots of sigon saag in Chakma, which is a plant that grows in the forest, especially in the DTR. According to him, it is illegal to do so, and if caught by the forest department of the DTR he will have to pay a heavy fine[3]. He explains that this plant was in the daily diets of people as a curry for a long period, and that his community never knew that the roots of the plant can be sold very expensively. One kilogram of dry roots of this plant is from a range of rupees 100 to 150 (1.4 to 2 USD) and according to him, if he works for a month then he can sell between 150 to 200 kilograms. He says that although it is considered illegal because of the DTR, it is available in other areas which are not under the reserve forest. He stated that “the DTR has taken away all of their community lands where they used to cultivate, and he can’t go and collect from the Mizo areas where it is available as it is their land, and therefore, we are compelled to do it even if it is illegal.” Moreover, he said that since he is neither a fisherman nor a hunter, he has no other alternative.

There are 20 (twenty) villages in and around the Dampa Tiger Reserve (DTR) forest belonging to the three indigenous peoples’ of the Mizo, Chakma, and the Reang. These twenty villages consist of 45,183 (forty-five thousand and one hundred and eighty-three) people with 8,742 (eight thousand seven hundred forty-two) households (Govt. of Mizoram, 2014). The core areas of the DTR belong to the Chakmas and the Reangs, while the buffer areas are in the communal land of the Mizo. The core areas are considered inviolate where no human activities are allowed. In the buffer areas, there are livelihood or other state sponsored economic activities such as plantations allowed. The state government too recognized that the buffer areas had important cultural and mythological significance among Mizos and other tribes. These buffer areas, also known as Supply Forest, provide the necessary timber and Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFP) such as firewood, fish, crab, wild vegetables, bamboo shoots, medicinal plants, honey, cane, and prawns, which helps in reducing the dependency on the Core areas. In the buffer areas, there are also several river and stream beds, which provide suitable microhabitats for biodiversity. It is also an important area as large numbers of agricultural crops that are unique to this agro ecological zone are found there.

The buffer areas for the Mizos and the core areas for the Chakmas and Reangs, clearly established the discriminatory practices of the DTR based on identity and ethnicity. In the later parts, the paper shall explore and explain why the Chakma and Reang communities are targeted and excluded in the decision-making process of the DTR. In the following, it shall discuss the process of making the DTR.

The DTR: People, Politics, and the State

The Dampa Tiger Reserve (DTR) conservation project is unwanted for the marginalized communities such as the Chakmas and the Reangs. The project is only wanted by the Mizos. It has become a source of conflict between the Mizos and the others. On 21st October 1997, Mr. Lalzawmliana, a Forest Game Watcher in Dampa Tiger Reserve (DTR) was murdered and two of his friends were also abducted by the Bru National Liberation Front (BNLF). This led to communal violence between the Mizos and the Reangs and ultimately the mass exodus of the Reangs or Brus from Mizoram state. This also resulted in the burning of 500 Bru’s houses and displacement of more than 33,000 Bru or Reang tribes in the neighbouring states of Tripura, and Assam.

On the other hand, the Chakmas believe that the DTR is not for the tigers, but to serve the state’s agenda of dismantling the political demands of the Chakma and Bru tribes. In the autonomy movement, the Chakmas demanded the inclusion of all the Chakma people and their habitats in the Chakma Autonomous District Council (CADC). It consisted of 31,000 Chakma from “the preponderantly Chakma-inhabited western Mizo Hills from Tuipuibari also known as Amsury and Rajivnagar in the north to Parva in the south and including Silsury, Marpara, Punkhai, Demagiri, Tuichang Ghat, Lungsen, Barapansuri, Chawngte, Jarulsari, Vasitlong, New Jaganasuri,” forming “the territorial jurisdiction of the autonomous district council for the Chakmas.” However, in 1972, while granting the Chakma Autonomous District Council (CADC), only 11,153 Chakma people were included and the rest living from Tripura border to Demagiri (Tlabung) areas were excluded. The Chakma leaders were not happy and protested the exclusion of the Chakma villages. The then Chief Commissioner of Mizoram, S.J. Das, tried to appease the Chakma leaders by stating that it was just an ad hoc arrangement and assured that their demand for inclusion of all the Chakma populated areas would be considered later.

In fact, the Mizos even opposed the creation of CADC. In 1986, while signing the Mizo Peace Accord between the Mizo National Front (MNF) and the Indian state, the MNF leader, Laldenga, asked the Government of India to abrogate the Chakma Autonomous District Council (CADC) to which the Indian government did not agree. The then Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi told him in a rally in Aizawl that “if the Mizos expect justice from India as a small minority, they must safeguard the interest of their minorities like the Chakmas” (Benerjee et. al., 2005). In fact, from 1985 to 2000, 21 private Members resolutions were submitted in the State Assembly for the abolition of the Chakma Autonomous District Council, out of which 7 were rejected, 14 were admitted, of which 2 resolutions were discussed and negated (Benerjee et. al. 2005). In August 1992, about 380 Chakma houses were burnt down by the organized mobs of the Mizos in the villages of Marpara, Hnahva, Sachan and Aivapui which are in and around the Dampa Tiger Reserve Forest. In a 2009 Asian Centre for Human Rights (ACHR) report, it states that on “30th of January 1995, the MZP (Mizo Zirlai Pawl) served “Quit Notice” to the Chakmas to leave Mizoram by 15th June 1995.”

In this way, the DTR has become a part of the web of ethnic conflicts and politics.

The people and the environment in Mizoram: A historical analysis

In the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHTs) of Bangladesh, the Dampa area is recognized under the Sazek or Sajek Hill Range which runs in a north-south direction between Dampa and Kasalong Reserve Forest with a forested area of no less than 4,000 km.² Wild animals migrate between Dampa and Kasalong Reserve. In pre-colonial and colonial times, this was a shared space for the wildlife and the people who kept moving from one place to another, across the borders, established in 1947, between India and Bangladesh. There were movements of people from hills to plains or lowlands and vice-versa whereby goods and services were exchanged, and the forms of life were neither distinct nor different ‘in contrast’ as ‘hills’ or ‘valleys.’

However, under colonial rule the process of identification and demarcation of areas and fixing of populations took place, though the people never maintained such a boundary. In the post-colonial times, after the coming of nation-states, when claims of absolute and relative space took hold, this space was claimed by all the tribes such as Mizos, Chakmas and Reangs who inhabit both sides of the border.

The Dampa represented fluidity and continuity of life between the hills and plains for the people and wildlife. The memories, lifeworld, and the worldviews of the Mizos and the Chakmas demonstrate their intimate relationship with nature or the environment. For example, the reasons for their migrations from the valleys to the hills are due to their experiences with environmental events such as floods, famines, and other natural calamities. The paper examines one of such environmental events, which is the Bamboo flowerings that played a decisive role in various historical periods such as the pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial times.

The Mizos and the Bamboo flowerings

The bamboo flowerings or the Mautam and Thingtam (in Mizo) are ecological cyclic events that occur every 48-50 years. Once it occurs it is followed by a plague of rats. There are two types of bamboo flowerings; one is known as Mautam which is due to the flowering of muli bamboo or Melocanna baccifera and the other one is the Thingtam which results due to the flowering of Bambusa tulda also known as Indian Bamboo or Bengal Bamboo. Both varieties of bamboo have a periodic life cycle of 48-50 years. These seeds are delicious foods for the jungle rats. Once the rats run out of bamboo seeds, however, they attack crops in the fields, resulting in food scarcity, starvation, diseases, and deaths (S. Nag, 1999).

Famines have historically resulted in acute shortages of food and forced the people to live on forest products such as roots, jungle yams, and other edible forest products. Alexander Mackenzie, 1884 records that in 1911-12, for instance, W.N Kennedy, the Deputy Commissioner of the Lushai Hills, borrowed a sum of Rupees 80,000 from the British government to help the famine victims. Indeed, the Bamboo flowerings that led to famine was an opportunity for the British including the Christian missionaries to bring the Mizo under their colonial administration and rule.

After India’s independence, the Lushai Hills Autonomous District Council under the Assam state passed a resolution to take precautionary measures against the famine that was predicted to be in the next year. The Council also asked rupees fifteen lakhs (1500,000) for relief measures (Liangkhaia: 2002; Parry: 1925Shah: 2000; Shyam: 2004). However, the Assam government rejected and ridiculed it by stating that such prediction or anticipation of famine is not scientific, famines could not be predicted, and the connection between bamboo flowering and increase in rodents is a tribal belief. As predicted, the Bamboo flowering struck the Lushai Hills District in 1959 and the Assam government was taken by surprise (Dhamala: 2002; Dokhuma: 1999; Ghosh: 1997; Hluna: 1994; Lalchungnunga: 1994; Lalrawnliana: 1995).

The famine brought deaths in large numbers due to starvation (Mackenzie: 1994; Veghaiwall: 1951; Verghese: 1996; Verghese: 1997; Zakhuma: 2001 Statistical Handbook of Mizoram: 2006; 2008; 201 0; Chatterjee: 1995; Vanlalhluna: 1985). The Assam state did not know how to handle the situation and sought help from the Indian Air Force to carry out relief measures. However, the supply of wheat to the rice-eating people and the faulty supply chain further created anger and hatred against the Assam government among the Mizo people. Rupees 190 lakhs (190,00000 rupees) were sanctioned for the relief works by the Assam government, but the cases of starvation and deaths kept increasing (Banik: 1998; Arya, Sharma, Kaur & Arya: 1999).

The Mizo cultural society, which was formed in 1955, changed into the ‘Mautam Front’ in 1960 where Laldenga was the secretary. The Mizo Youths who were involved in relief works in towns and the remote villages led by Laldenga. They became popular among the people. On the one hand, neither the Assam state had any idea how to respond to such natural calamities, nor did the Indian government. At the same time, the Assam state came up with the imposition of the Assamese language by making Assamese a state language that was not spoken in the then Mizo district by the people. This led to great disappointment in the Mizo district and the political movement to demand separation started.

In September 1960, the Mautam Front was renamed the Mizo National Famine Front (MNFF) and gained popularity among the people in Mizoram and outside and on 22nd October 1961, the MNFF converted into a political party as Mizo National Front (MNF). On the 28th of February 1966, the MNF formed the Provisional Government of Mizoram. On the 1st of March 1966, the MNF declared the independence of Mizoram from India. On the 6th of March 1966, the MNF was declared an unlawful organization and the Mizo District as a ‘disturbed area.’ The Indian state responded with extreme measures including attacks by fighter jets. Such extreme steps by the Indian state could not destroy the movement and resulted in guerrilla warfare that lasted over 20 years. The Lushai Hills District Council was given the status of Union Territory in 1972 and finally, after twenty years of struggles, the movement succeeded in achieving statehood on 20th February 1987.

After Mizoram state formed, the first Bamboo flowerings took place in 2007-2008. Like before, this resulted in a dramatic increase of rats who attacked the crops and other agricultural products. The Agriculture Department of Mizoram (2009) reported that it affected 1,30,21 hectares households in 769 villages and the rats had damaged 12,93,476 quintals of Jhum paddy cultivation. The Department estimated the losses at Rs 411.38 crores. While the loss in paddy was 89.76 per cent, the loss in other crops such as maize and vegetables was about 60 percent (Talukdar, 2008). However, the Mizoram state started planning and preparation in advance in 2004 to combat the 2007-2008 bamboo flowerings. The state government launched a special programme named Bamboo Flowering and Famine Combat Scheme (BAFFACOS) with the help of the central government (Trivedi et al., 2002). Although, the effects of the Bamboo flowerings were not severe unlike in the previous times, there were allegations of large-scale corruption. As a result, in the 2009 State Assembly Election, the then Mizo National Front (MNF) government suffered by winning only 2 (two) seats out of the 40 seats.

The interactions or relationships of the tribal people with nature is symbiotic, time tested, and which has been perfected over times and space. The environmental events of Bamboo flowerings demonstrate how the tribal people intrinsically connected with the local environment and how it is significant to their socio-cultural and political lifeworld. The approach of conservation paradigm to conserve biodiversity, addressing climate change, and environmental challenges by imposing and forcing the local people and environment shall lead to the creation of more challenges.

Conclusion

The most celebrated countryside of Europe and its environment is the product of people’s relationships with nature that have evolved over centuries. Imagine, declaring the European countryside as some wildlife sanctuaries or reserve areas for conservation projects and displacing the local people. To do so is even beyond imagination. However, it does not matter for the people and the environment in the global south, and especially in the geographies of Indigenous peoples. What matters is the decision and policies of conservation by powerful states and institutions. In doing so, local peoples are either displaced from their land or taught how to conserve by making them participants in the implementation of the conservation projects.

This paper demonstrated how the state-led conservation practices can be very coercive on the populations in and around the area in which the conservation project is set up. The DTR is a fictitious conservation project to protect tigers where there are no tigers. It is an instrument of socio-political power for the state and the dominant social groups against the other ethnic minorities in Mizoram. A project like the DTR is a conservation discourse fantasy just like the “development discourse fantasy” coined by Ferguson.

The imposed conventional ideas of conservation practices are seen and considered top-down, instrumental, forceful, and colonial which breaks the local socio-ecological systems and disrupts people’s lives. It consequently develops an antagonistic relationship between the local people and the conservation projects. The conservation project framework is often taken for granted by world powers and institutions for a way forward to climate change.

This paper also demonstrated why the relationship between nature and local culture is inseparable from understanding the environment and conservation. It illustrates how nature shapes people’s lifeworld, and in turn how people shape the local ecology. In the process, the local people’s social consciousness inherently gets constructed by their relationships with nature. For instance, the Bamboo flowerings showed how environmental events play a determinant factor in socio-cultural and political life. The conservation project framework fails to understand the deep relationships of the local people with nature. It also either ignores or fails to understand the complex socio-cultural, socio-ecological, socio-political, and cultural relationships contextualised by state, market, and social relationships and realities in different parts of the world. Hence, it ends up imposing foreign or colonial conservation practices, creating profound crises for both biodiversity and sustainability.

[1] Interviews on 20th May 2018 in the village Silsury with Chandra Hasso Chakma of 65, Harishchand Chakma of 70, Guluk Dhan Chakma of 67, and Bulow Chakma of 67 years old. On 25th May 2018 interviews in the village Hnahva (Hnahva village was displaced in 1989-90 from the DTR forest) with Amarchand Chakma of 68, Dino Chakma of 69, Haraw of 60, and Bindu Chakma of 65 years old.

[2] Name is anonymous for the safety and security of the interviewees.

[3] The activities in the DTR are regulated by the Section 39 of the Indian Forest Act, 1927 which gives jurisdiction to the state to regulate and govern over the public and private forests. The Act also to consolidate the laws relating to forests, regulate and transit forest produces and to levy duty on timber and other forests produce.

Bibliography

Bill Adams, Green Development: Environment and Sustainability in a Developing World (Routledge, 2008).

Christopher, Stephen. “‘Scheduled Tribal Dalit’ and the Recognition of Tribal Casteism.” Journal of Social Inclusion Studies: The Journal of the Indian Institute of Dalit Studies 6 no. 1 (2020):1 –17.

Adhikari, Upendra. “BAMBOO FLOWERING HUMAN SECURITY AND THE STATE: A Political Ecological Study of the Impact of Cyclical Bamboo Flowering on Human Security and the Role of State in Mizoram.” Shodhganga. Information and Library Network, 2013. https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/jspui/handle/10603/165868.

Ferguson, James. “The Anti-Politics Machine: ‘Development,’ Depoliticization, and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho.” Choice Reviews Online 28, no. 04 (December 1, 1990): 28–2279.

Hunter, W. W. A Statistical Account of Bengal, 1875.

Kumar, Anil, and P. S. Ramakrishnan. “Energy Flow through an Apatani Village Ecosystem of Arunachal Pradesh in Northeast India.” Human Ecology 18, no. 3 (September 1, 1990): 315–36.

Lalthangliana, B. History of Mizo in Burma, 1980.

Lewin, Thomas Herbert. A Fly on the Wheel: Or, How I Helped to Govern India, 1885.

Environment, Forests & Climate Change Department. (n.d.). https://forest.mizoram.gov.in/page/wildlife-of-mizoram

Nag, Sajal. “Bamboo, Rats and Famines: Famine Relief and Perceptions of British Paternalism in the Mizo Hills (India).” Environment and History 5, no. 2 (June 1, 1999): 245–52.

Nguu, N. V., and R.K. Palis, “Energy input and output of a modern and traditional cultivation system in lowland rice culture, Kalikasan, Philippines,” Journal of Biology 6, no. 3 (1977): 1-8

Poirier, Robert A., and David Ostergren. “Evicting People from Nature: Indigenous Land Rights and National Parks in Australia, Russia, and the United States.” Social Science Research Network, April 7, 2003.

Rogers, Finlay. ZO History, Mizo, Kuki, The Chin. Blurb, 2020.

- Chatterjee et al., “Background Paper on Biodiversity Significance of North East India for the study on Natural Resources, Water and Environment Nexus for Development and Growth in North Eastern India.” WWF-India, New Delhi, 30 June 2006.

Shyamal, B. C. “Tiger Conservation and Its Impact: A Study of Dampa Tiger Reserve (DTR) in Mizoram”, MA Dissertation at Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, 2013.

- R. Shankar Raman, “Effect of Slash-and-Burn Shifting Cultivation on Rainforest Birds in Mizoram, Northeast India,” Conservation Biology15, no. 3 (June 1, 2001): 685–98.

Zaitinvawra, David, and Kangaraj Easwaran. “Hunger and Public Action: Government’s Response to Bamboo Flowering in Mizoram Development of North East.” Edited by R. P Vadhera. Manglam Publishers & Distributors, New Delhi. 2 (April 7,2016):511-25.

[1]Mizoram (2023), https://forest.mizoram.gov.in/page/wildlife-of-mizoram.

[2] Interviews on 20th May 2018 in the village Silsury with Chandra Hasso Chakma of 65, Harishchand Chakma of 70, Guluk Dhan Chakma of 67, and Bulow Chakma of 67 years old. On 25th May 2018 interviews in the village Hnahva (Hnahva village was displaced in 1989-90 from the DTR forest) with Amarchand Chakma of 68, Dino Chakma of 69, Haraw of 60, and Bindu Chakma of 65 years old.

[3] Name is anonymous for the safety and security of the interviewees.

[4] The activities in the DTR are regulated by the Section 39 of the Indian Forest Act, 1927 which gives jurisdiction to the state to regulate and govern over the public and private forests. The Act also to consolidate the laws relating to forests, regulate and transit forest produces and to levy duty on timber and other forests produce.

Author

Shyamal Bikash Chakma, PhD, School of Oriental and African Studies

(No Ratings Yet)

(No Ratings Yet)